Learning by Making

There is a kind of learning that cannot be thought through in advance.

It has to be felt. Touched. Lived in the hands.

Returning to making — properly making — has reminded me of this in the most grounding way. Not as a concept, but as an embodied truth. When I work with unfamiliar materials, thinking loosens its grip. Control softens. Something else takes over.

This is where learning actually happens.

I have spent decades working with a high level of technical fluency. That experience does not disappear when I step into new territory — it hums quietly beneath the surface. What has shifted is my relationship to outcome. I am no longer trying to resolve ideas immediately. Instead, I allow them to arrive through action.

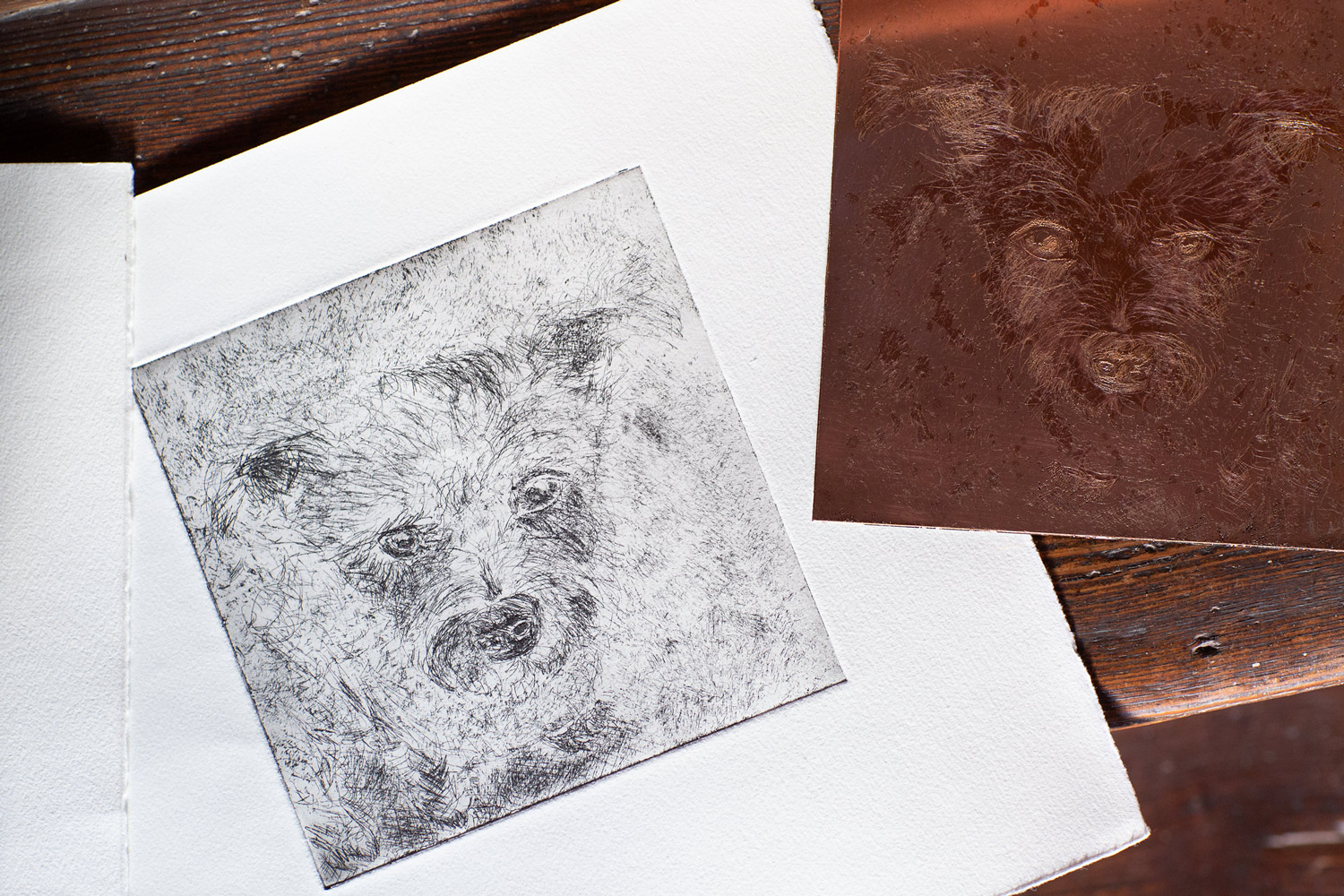

Working with lino, copper, zinc, paper, and ink — materials that resist, respond, and surprise — has been humbling and exhilarating in equal measure. Each surface demands attention. Each mark carries consequence. There is no shortcut to understanding; the material teaches as it is handled.

This way of working feels refreshingly honest. There is no performance of certainty. No need to justify decisions before they are fully formed. Instead, there is a dialogue — between hand and surface, instinct and resistance.

I am reminded that photography, too, was once learned this way. Through repetition. Through failure. Through staying close to the work long enough for understanding to arrive. Mistakes are not interruptions here. They are information.

What matters most at this stage is not what the work is, but what it is teaching me — about pace. About attention. About trust. About letting go of polish in favour of presence.

There is a quiet confidence in allowing myself to be a beginner again — not because I lack experience, but because I no longer need to prove it.

This is learning by making.

And it feels like coming home.

I find myself working in sequences rather than singular pieces — printing, reworking, altering pressure, changing inks, scraping back, starting again. What emerges is not refinement in the traditional sense, but awareness: of what the material wants, and what I am asking of it.