Before photography became fast, it was slow — and I learned that pace in the darkroom.

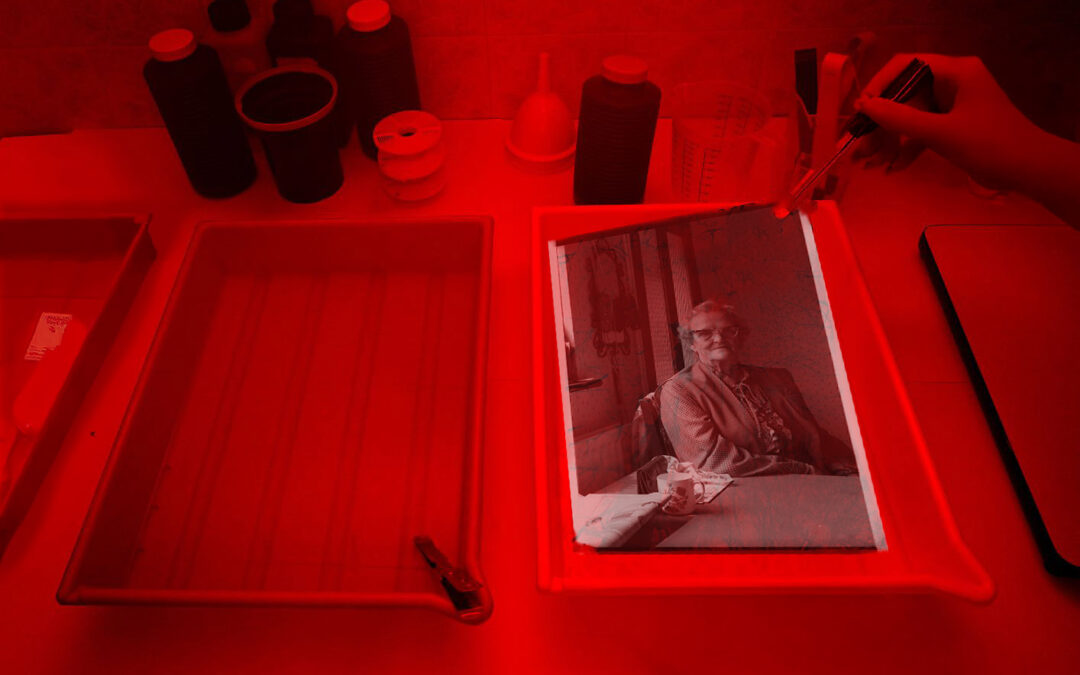

The darkroom was my secret, sacred space. Almost womb-like in its protection from the outside world. Just me, my negatives, and the heady, familiar smell of developer, stop bath, and fixative. Me and my thoughts, and a practice honed over years of devotion to the craft. Pure alchemy.

There are no words that can fully encompass the feeling of placing a dormant image into the first tray — watching, waiting, not quite knowing if you’ve got it right. And then, when you have, the quiet surge of joy. When you know, you know.

The darkroom taught me patience. It demanded it. There was no rushing to be had — shortcuts would inevitably reveal themselves, if not immediately then years later, when a print began to turn an unfamiliar shade. Working this way slowed me down and required me to truly be with the work. To absorb it. To look. To reflect.

It was a solitary place, and the process became almost meditative. Long hours passed unnoticed as images emerged and decisions were made carefully, deliberately. Looking back, that time and space allowed me not only to reflect on my photographs, but on life itself. Printing is a hungry, all-consuming process — and it required my full attention.

What I see now is how perfectly this slowness balanced the intensity of shooting. The energy of a photographic session — fast, responsive, emotionally charged — is exhilarating. I love it with every cell in my body. But I am, at heart, an introvert. My more sensitive, reflective side needs an equal counterweight. The darkroom provided that balance beautifully.

Some of my clearest memories live there. Rain pounding on the roof above — my darkrooms always seemed to find themselves tucked into attic or roof spaces — working late into the night, losing all sense of time. In those moments, my analytical mind would quieten, and instinct would take over. That was where the gold was made.

I even remember noticing that on nights with a full moon, I could taste metal from my silver fillings — a strange, sensory detail that has stayed with me long after the fillings themselves have been replaced. Funny what the body remembers.

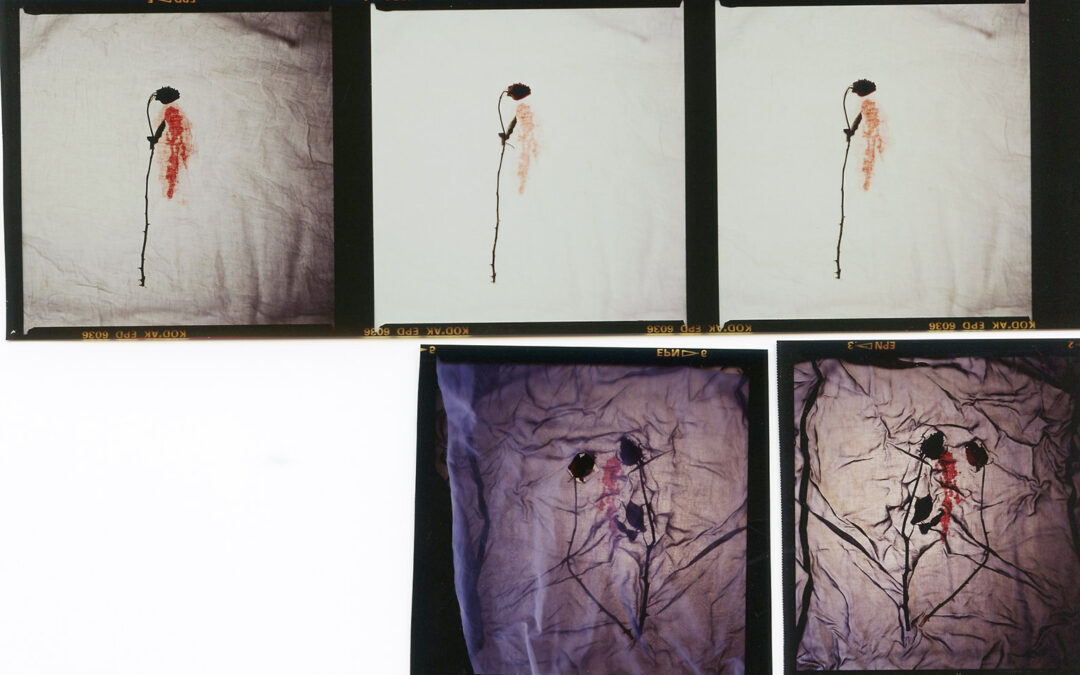

My business has been fully digital for many years now, yet I find myself increasingly yearning for the analogue to return. I’ve already dusted off my original Nikon 35mm and my Canon EOS 3 — faithful old friends — and begun experimenting again with rolls of long-expired film still tucked away from those earlier years.

I feel fortunate to belong to a generation that grew up with analogue, pivoted to digital at the right moment, and now has the perspective to choose intentionally what comes next. With experience behind me, and curiosity still intact, I can sense the direction my practice is moving toward.

This is not nostalgia.

It is a return to slowness, materiality, and intention.

Watch this space.